|

The circumstances of Andreas Vesalius’ death in Zakynthos in 1564 may have been described in one of two differing accounts, originally written by three different men between the years 1565 and 1573, in five different texts. No additional information from people who may have been in possession of some facts is known to have survived.

In two of those texts the writer Petrus Bizarus claims that a travelling goldsmith found the great anatomist abandoned in a miserable hut on a deserted beach, dying from an unspecified illness (1). The unnamed goldsmith, in spite of strong opposition from the locals, buried him with his own hands in a plot of land he purchased for that purpose.

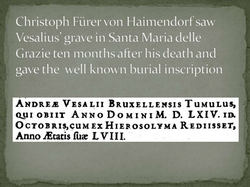

The veracity of Bizarus’ account appears doubtful due to its pervasive vagueness and the improbability of such treatment of an important nobleman by both, the Venetian authorities of Zakynthos and his own companions. More importantly it is incompatible with the testimonies of Christoph Fürer von Haimendorf (2) and Giovanni Zuallardo (3) , who saw Vesalius’ tomb at the Franciscan monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, in 1565 and 1586 respectively. Their testimonies are also supported by that of Filippo Pigafetta (4). From their descriptions it is obvious that Vesalius was buried with some decorum and his grave was not dug simply to prevent the desecration of the body by wild animals.

.

|

Pavlos Plessas

Click on the image for author information

|

|

In a rather unexpected way this account’s credibility is further strengthened by the astonishing events it describes. For if someone is to present a fabricated account it is natural to try and make it as believable as possible. Even if the aim is to impress or to shock, the disturbing inventions have to have plausible and uncomplicated explanations. Contrary to this we are told of a ship that was unable to reach land for forty days, of severe food and water shortages, the consequent outbreak of an illness that caused many deaths but strangely affected only the pilgrims, Vesalius becoming depressed and anxious – which in the belief of Metellus contributed to his illness – his pleading to the crew to not bury him at sea, and finally his death as soon as they reached land – a very sudden collapse by the city gate according to Metellus. It will be shown that this sequence of extraordinary events has a reasonable, quite likely even, and singular explanation.

|

Click on the image for a larger depiction

|

| Article continued here: Powerful indications that Vesalius died from scurvy (2)

Sources and author's comments:

1. Historia di Pietro Bizari della guerra fatta in Ungheria dall'invictissimo imperatore de'christiani contra quello de'Turchi, Lyons, 1568, p. 179; also in his Pannonicum bellum, Basel, 1573, p. 284.

2. Itinerarium Aegypti, Arabiae, Palaestinae, Syriae, aliarumque Regionum Orientalium, Nuremberg, 1621, p.2

3. Il devotissimo Viaggio Di Gierusalemme, Rome, 1595, pp. 85 – 86.

4. Theatro del Mondo di A. Ortelio: da lui poco inanzi la sua morte riveduto, e di tavole nuove et commenti adorno, et arricchito, con la vita dell' autore. Traslato in lingua Toscana dal Sigr F. Pigafetta, 1608/1612, background information to Map 217. Pigafetta, commenting almost two decades after his visit to Zakynthos in July 1586, mistakenly named the burial place of Vesalius as the monastery of St Francis. However, he leaves no doubt with regards to which monastery he actually meant by corroborating Zuallardo’s story of the inscription’s looting by the Turks in 1571. There was indeed a St Francis monastery in Zakynthos. It was, however, inside the castle and, hence, it was never looted by the Turks. Santa Maria delle Grazie on the other hand was in the area that is known to have been looted. I am grateful to Marcel van den Broecke for sending me photographs of the original text kept in the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in Hague.

5. Metellus’ letter to Georgius Cassander was published in Petrus Bertius’ Illustrium & clarorum Virorum EPISTOLAE SELECTIORES, Superiore saeculo scriptae vel a Belgis, vel ad Belgas, Leyden 1617, pp. 372 – 373. His short letter to Arnoldus Birckmannus is unpublished though an English translation is in Charles Donald O'Malley’s Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. A photocopy was kindly provided by the Cushing/Whitney Medical Historical Library of Yale University and a transcript made by Maurits Biesbrouck.

6. Maurits Biesbrouck, Theodoor Goddeeris and Omer Steeno, The Last Months of Andreas Vesalius: a Coda, Vesalius – Acta Internationalia Historiae Medicinae, Vol. XVIII, No 2, December 2012, pp. 70 – 71, from Thomas Theodor Crusius’ Vergnügung müssiger Stunden,oder allerhand nutzliche zur heutigen galanten Gelehrsamkeit dienende Anmerckungen of 1722.

7. The monastery of St Elias was on the hill high above the port and St Franciscus even higher, inside the castle. St Mark was built later, in the 17th century.

|