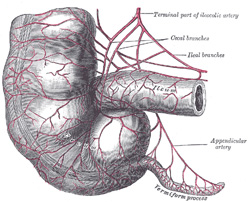

Terminal ileum, cecum,

and vermiform appendix

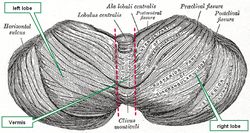

The word [vermis] is Latin and means "worm". The term [vermiform appendix] means "the worm-shaped appendage", and refers to a worm-like appendage that is related to the cecum, a segment of the right colon.

This structure was first described by Jacobo Berengario da Carpi in 1524, and it was Andreas Vesalius who first described it as an appendix, and suggested it looked like a worm. It has been called the [vermix] and the [cecal appendix]

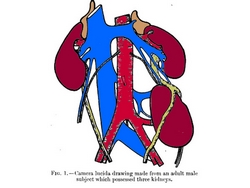

The vermiform appendix* has the same four layers found in most of the abdominal digestive tract and is attached to the cecum at the point where the three tenia coli (libera, mesenterica, and omentalis) meet. The length of the vermiform appendix is variable. On average about 2.5 to 3 inches, it can be as long as 10 inches in length, with one recorded case of a 13 inch appendix!**

The location of the vermiform appendix is also subject to anatomical variation, being found in a retrocecal position in 65% of the cases. For more information on this organ's anatomical variations, click here.

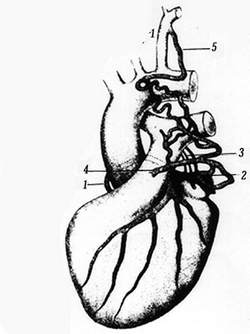

The vermiform appendix is an intraperitoneal structure, as it has a peritoneal extension called the mesoappendix. Within the mesoappendix are the appendiceal arteries and veins. The appendiceal artery is usually a branch of the ileocolic artery.

Sources:

1. "The Origin of Medical Terms" Skinner, HA 1970 Hafner Publishing Co.

2. "Medical Meanings - A Glossary of Word Origins" Haubrich, WD. ACP Philadelphia

3 "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8 Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

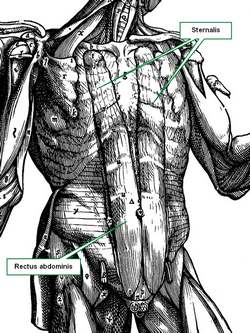

4. "Anatomy of the Human Body" Henry Gray 1918. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger Image modified by CAA, Inc. Original image by Henry Vandyke Carter, MD., courtesy of bartleby.com

*. It is not proper to call this structure the "appendix", as there are many appendices in the human body.

**. Personal note: The longest vermiform appendix I have personally seen was 8 inches (20.3 cm) in length, retrocolic, and the tip of the organ was actually retrohepatic!. Dr. Miranda.