|

Metellus and Solenander agree on most of the details of the story, to the point that it appears the initial source of their information was the same person, however, their versions are not identical. Metellus claims to have received his information from Georgius Boucherus in person, in the presence of a reliable witness, while we do not know how many times the story was recounted before reaching Solenander. Hence, while Solenander provides some valuable information, it is Metellus’ version, notwithstanding his conjectures, that should be considered more faithful (8).

It is very clear from both versions that, some weeks into the journey, a disease broke out on board the ship. Also, more clear in Metellus than in Solenander, that Vesalius was a victim of the same disease, which was somehow connected to food and water shortages..

|

Click on the image for a larger depiction

|

| (Based on the above) It can be easily concluded that the mysterious outbreak does not appear to have been due to contagion on board the ship. Neither the crew was affected nor Boucherus developed symptoms, either during the voyage or in the following months, in spite of his close proximity with the patients for at least forty days. Consequently, the disease was the result of either a pathogenic factor the pilgrims came in contact with or of some nutrient deficiency.

Contact with a pathogenic factor should have happened before boarding the ship, with the possible exception of the pilgrims consuming contaminated food that was not available to the crew. That way they could have fallen ill with typhoid fever, which has a variable incubation period of up to 30 days. However, complications and death from typhoid usually occur in the third week of the illness, which would have been near the end of the journey. Vesalius would simply not have had the time to get worried, fall ill, develop complications and die by the time they reached land. His sudden collapse and death does not fit in well with typhoid either.

|

| Looking for pathogenic factors on land we can distinguish between vector borne diseases and poisoning. It is, however, inconceivable that the victims of some 16th century poison would have shown no symptoms for weeks after receiving a lethal dose. Therefore, only vector born diseases need be considered and from those only the ones that are very deadly and present in the region. None of these though agree with what Metellus let us know about the disease.

When considering the various nutritional deficiencies we only need to deal with those that could have led to multiple deaths within six weeks from the onset of obvious physical symptoms, and could conceivably have appeared under the prevailing conditions of the journey and the socioeconomic and cultural traits of the region. As such, only scurvy appears to fulfil the criteria. Many may think that even scurvy is not a good candidate since a six week sailing is not thought sufficient for its appearance.

|

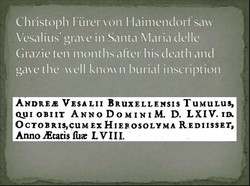

Click on the image for a larger depiction

|

| In fact, very often scurvy did not take long to appear or cause deaths. According to the naval physician Thomas Trotter it was common for an 18th century British warship of the Channel Fleet to lose up to a dozen seamen to scurvy and have another fifty hospitalised during a cruise of just eight weeks (9). A scurvy patient on a ship rarely survived for seven weeks and many died much earlier (10).

Also, it has to be pointed out that Vesalius’ journey did not last only weeks; he left Venice sometime before the 24th of May (11) and died in Zakynthos in the middle of October, a minimum of five months. More than two of these he spent sailing and the remainder in semi-desert or desert conditions. The Holy Land in Vesalius’ time was arid and mostly barren, especially in the high summer. Many pilgrims, shocked by what they saw, believed the area had been cursed by God (12). No vegetables grew at that time of year and only some grapes, grown by Christians, and figs, growing wild, could have been ripe. Both fruit contain very little Vitamin C (13).

Article continued here: Powerful indications that Vesalius died from scurvy (3)

Sources and author's comments:

8. There are additional reasons for this. In Solenander’s version there are efforts to explain certain aspects of the story, which may have been nothing but an intermediate informant’s speculation passed on as reliable information. An example of this is that, according to Solenander, Boucherus met Vesalius and the other pilgrims in Venice, and travelled with them to Cyprus where they separated. He went to Egypt while they continued to Jerusalem. On his return journey he travelled again via Cyprus and by coincidence met the same companions on the same ship. All this is possible but unlikely, especially if he meant that the ship waited for the pilgrims for three months. There is even the suspicion that at least one part of the original story was intentionally “corrected”: Metellus says that Vesalius collapsed and died soon after disembarking, while Solenander says he died on board the anchored ship. Conventional wisdom dictates that a very sick man does not disembark and walk on the shore of Zakynthos but expires on board his ship. This is not always true but the temptation to perform a little cosmetic surgery on the story is understandable.

9. Medicina Nautica: an Essay on the Diseases of Seamen, Volume III, London 1803, p. 387.

10. James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy, London 1772, p. 281.

11. This is the publication date of the Examen, in the preface of which Francesco dei Franceschi recalls Vesalius’ visit to Venice.

12. Felix Faber’s description is typical: But even I said secretly in my heart: see, this is the land that is supposed to flow with milk and honey; but I see no fields for bread, no vineyards for wine, no gardens, no green meadows, no orchards, but it is all rocky, burnt by the sun and parched.

13. Figs contain about 2 mg per 100 g; grapes 3.2 mg. Data from the United States Department of Agriculture. A man whose body stores of Vitamin C are very low will need to eat 10 – 12 figs or more than 60 grapes every day just to remain above the threshold of scurvy.

|