|

The azygos lobe, also commonly referred to as the" accessory lobe of the azygos vein", was first described in 1877 by Heinrich Wrisberg. It is seen in 0,4 % of chest X-rays; 1,5% in high resolution CT, and 1% in anatomical dissections. It is not a true accessory pulmonary lobe as it does not have its own bronchus and does not correspond to a specific bronchopulmonary segment, the “azygos lobe”, is located at the apicomedial portion of the upper right lobe and it separated from the remainder of the upper lobe by a fissure (Denega et al, 2015; Özdemir et al, 2017)

A convex-shaped fissure is created by the course of the vein bearing towards the medial side of the right lung to join with the superior vena cava. Its formation is a result of an unusual embryogenic migration of the posterior cardinal vein; which is a precursor of the azygos vein (Denega et al, 2015).

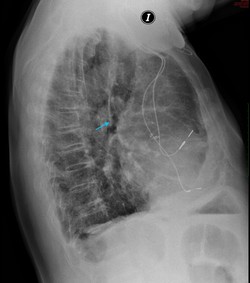

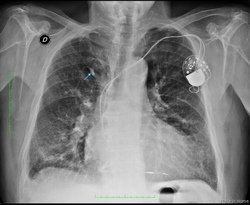

Instead of sliding over the lung medially, the vein invaginates into the parenchyma of the lung and becomes enveloped by layer of pleural folds, forming a mesentery-like structure, also called “mesoazygos”. Further migration into the lung as it passes towards the right hilum creates a convex semicircular fissure with the vein located at the base of the fissure. This fissure can be identified in an X-ray chest image as a coma-shaped (“Teardrop sign”) or curved linear shadow in the paramediastinal region of the right lung; it terminates at the level of second costal cartilage (Akhtar et al, 2018; Caceres et al, 1993). The lower portion of the azygos fissure is teardrop-shaped and its contains the azygos vein (Özdemir et al, 2017; Kotovet al, 2017).

The pathway of the vein within the lung is subject to individual variation, and this defines the position of the fissure within the apex of the upper lobe. The most superior portion of the fissure adopts a triangular form, called the trigone. The localization of the trigone determinates the size of the azygos lobe (Caceres et al, 1993; Fuad & Mubarak, 2016 ). A Left azygos lobe has been reported, but it is extremely rare (Özdemir et al, 2017)

Diagnosis of the azygos lobe may be complicated by morphologic variants of the fissure, physiological changes in the size of vein, and the projection of additional shadows within the lobe which may be misinterpreted as scar tissue, a calcified area of a post-infection process, or a malignant tissue or nodule.

|

Images provided by the authors. Click on the image for a larger depiction

|

| It usually has no clinical implications and is an incidental finding in images but the azygos vein may undergo physiological variations, reflected by changes in the size of its shadow and its position in the imaging studies. Expiration, the Valsalva maneuver, or the upright position effect on the venous return to the heart, may enhance the size of the vein and its shadow. Changes in intrathoracic pressure may result in the “empty azygos fissure” phenomenon, in which the medial displacement of the azygos vein occurs after the reexpansion of the collapsed lung, secondary to pneumothorax or pleural effusion as well as a shortened mesoazygos.

In rare cases the azygos veins may undergo variceal changes that are usually located in the arc of the vein. They remained asymptomatic or may be accompanied by a “pressure like” or “tightness” sensation within the chest, recurrent hemoptysis with bright red blood dry cough and dyspnea. The initial differential diagnosis includes acute myocardial infarction, aortic dissection and myocarditis. On the chest X-ray it may present as a round or oval paratracheal shadow with a smooth surface or outline. Untreated, it may predispose the patient to the risk of rupture, thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism. Azygos thrombosis is extremely rare and most cases in the literature had an undelaying azygos dilation or some prothrombotic status like malignancy. In all lung tissue some pathological process can originate in the azygos lobe as bullous, bronchiectatic changes, pneumonia and tuberculosis. (Kotov et al, 2018; Denega et al, 2015)

Otherwise, it seems the mesoazygos fold serve as a barrier to dissemination of the infection or malignant cells.

For thoracoscopic procedures, recognition of the azygos lobe is particularly important as it can cause partial obstruction of the surgical site view during thoracoscopic sympathectomy. In the literature, two cases have been reported where the phrenic nerve was coursing within the azygos fissure (Kauffman et al, 2010; Pradhan, 2017; Özdemir et al, 2017; Paul, Siba & James, 2018)

Thoracic surgeons as well as treating physicians need to be aware of this rare anatomical variation.

NOTE: For an explanation of the etymology of the word "azygos" click here.

Sources:

1. Akhtar, Jamal & Lal, Amos & B. Martin, Kevin & Popkin, Joel. (2018). Azygos lobe: A rare cause of right paratracheal opacity. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports. 23. 10.1016/j.rmcr.2018.02.001.

2. Caceres, Jennelyn & Mata, Jonathan & Alegret, X & Palmer, J & Franquet, T. (1993). Increased density of the azygos lobe on frontal chest radiographs simulating disease: CT findings in seven patients. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 160. 245-8. 10.2214/ajr.160.2.8424325.

3. Denega T, Alkul S, Islam E, Alalawi R. (2015). Recurrent hemoptysis - a complication associated with an azygos lobe. The Southwest Respiratory and Critical Care Chronicles, [S.l.], v. 3, n. 11, p. 44-47. ISSN 2325-9205.

4. Fuad, A.R., & Mubarak (2016). Two Cases of Azygos Lobe with Normal and Aneurysmal Azygos Vein on Computed Tomography. Int J Anat Res 2016, Vol 4(1):1843-45. ISSN 2321-4287

5. Kauffman, Paulo & Wolosker, Nelson & De Campos, José Ribas & Yazbek, Guilherme & Biscegli Jatene, Fábio. (2010). Azygos Lobe: A Difficulty in Video-Assisted Thoracic Sympathectomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 89. e57-9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.030.

6.Kotov G, Dimitrova I N, Iliev A, et al. (2018). A Rare Case of an Azygos Lobe in the Right Lung of a 40-year-old Male. Cureus 10(6): e2780. doi:10.7759/cureus.2780

|