|

The normal components of the aortic valve are part of the aortic root. The valve is composed of three leaflets, each of which are related to a sinus of Valsalva, and three interleaflet triangles. The anatomy of the aortic root, the aortic valve and the interleaflet triangles of the aortic root have been described in other articles in this website.

A bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is probably the most common cardiac defect of congenital origin. The prevalence of BAV ranges from 0.9% to 2% in the general population with a 3:1 male-female ratio.

In spite of the anomaly, a BAV may achieve normal valvular function, but this probably does not last, as BAV tend to develop calcifications in the adult leading to valvular disease, dysfunction, valvar stenosis, so complications are common, the most common being dilation of the aortic root and ascending aorta.

|

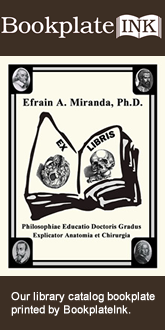

Excised bicuspid aortic leaflets.

Click on the image for a larger version. |

| The etiology of a BAV is commonly accepted as congenital and there are some studies that demonstrate a familial component, but it can appear in families where there is no known history of BAV.

There are several attempts at classifying BAV, as the leaflets that fuse are different, and so is the way of fusion.

There is one rare BAV called “pure”. This purely BAV is a true BAV, composed of two leaflets of similar size where there is no clear fusion line or “raphe” between the fused leaflets (see image). This valve has two well developed interleaflet triangles and the third can be absent or vestigial. The image depicts the excised calcified leaflets where the left and right coronary cusps are fused.

Other types of BAV have a well-developed raphe, have two well developed interleaflet triangles and the third may be large or anomalous. The leaflets may also be asymmetrical. The classification of the different types of BAV goes beyond the objective of this article, but they can be studied in the references at the end of this article. There is no doubt that the different types of BAV can cause valvar disease and hemodynamic chaos, so the surgical approach for these may be different, including valve repair, aortic annuloplasty, interleaflet triangle remodeling, and of course valve removal and prosthetic implant, either biological or mechanical.

Clinically, the pathologies related to the function of the aortic valve are stenosis, valvular incompetence, and in some cases intimal aortic dissection, which is a catastrophic complication. Some of these complications are triggered by the calcification of the bicuspid leaflets. Interestingly, although BAV is a congenital disease, only one in fifty children known to have BAV have clinically significant disease by adolescence.

PERSONAL NOTE: I have permission to publish the image in this article… because the bicuspid aortic valve depicted in this article is my own. My personal thanks to the medical and support personnel at the Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute, in Houston, TX., and my three cardiovascular physicians without whom I would not be back writing this article, Drs. Randall K. Wolf (contributor to this website), Dr. William Ross Brown (cardiologist), and Dr. Tuyen Nguyen, who operated on me. Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. “Etiology of bicuspid aortic valve disease: Focus on hemodynamics: Atkins, SA, Sucosky, P World J Cardiol. 2014 Dec 26; 6(12): 1227–1233.

2. “A classification system for the bicuspid aortic valve from 304 surgical specimens” Sievers, HH., Schmidtke, C. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:1226-33

3. “Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease” Siu, SC, Silversides, CK. JACC Vol. 55, No. 25, 2010:2789 – 800

4. “Bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy in adults: Incidence, etiology, and clinical significance” Int J Card 2015:1;400-407

5. ”Sutureless valve in freestyle root: new surgical valve-in-valve therapy” Villa E, Messina A et al. Ann Thorac Surg 2013:96:e155–e157

6.” Sutureless aortic bioprosthesis valve implantation and bicuspid valve anatomy: an unsolved dilemma?” Lona, M, Guichard JB, et al Heart vessels 2016.31:1783-1789

|