Medical Terminology Daily (MTD) is a blog sponsored by Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. as a service to the medical community. We post anatomical, medical or surgical terms, their meaning and usage, as well as biographical notes on anatomists, surgeons, and researchers through the ages. Be warned that some of the images used depict human anatomical specimens.

You are welcome to submit questions and suggestions using our "Contact Us" form. The information on this blog follows the terms on our "Privacy and Security Statement" and cannot be construed as medical guidance or instructions for treatment.

We have 398 guests and no members online

Jean George Bachmann

(1877 – 1959)

French physician–physiologist whose experimental work in the early twentieth century provided the first clear functional description of a preferential interatrial conduction pathway. This structure, eponymically named “Bachmann’s bundle”, plays a central role in normal atrial activation and in the pathophysiology of interatrial block and atrial arrhythmias.

As a young man, Bachmann served as a merchant sailor, crossing the Atlantic multiple times. He emigrated to the United States in 1902 and earned his medical degree at the top of his class from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia in 1907. He stayed at this Medical College as a demonstrator and physiologist. In 1910, he joined Emory University in Atlanta. Between 1917 -1918 he served as a medical officer in the US Army. He retired from Emory in 1947 and continued his private medical practice until his death in 1959.

On the personal side, Bachmann was a man of many talents: a polyglot, he was fluent in German, French, Spanish and English. He was a chef in his own right and occasionally worked as a chef in international hotels. In fact, he paid his tuition at Jefferson Medical College, working both as a chef and as a language tutor.

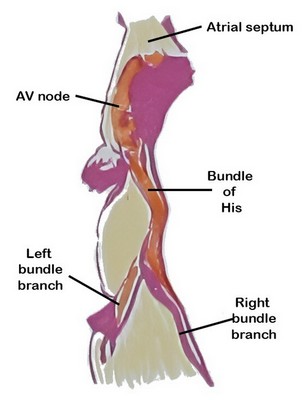

The intrinsic cardiac conduction system was a major focus of cardiovascular research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The atrioventricular (AV) node was discovered and described by Sunao Tawara and Karl Albert Aschoff in 1906, and the sinoatrial node by Arthur Keith and Martin Flack in 1907.

While the connections that distribute the electrical impulse from the AV node to the ventricles were known through the works of Wilhelm His Jr, in 1893 and Jan Evangelista Purkinje in 1839, the mechanism by which electrical impulses spread between the atria remained uncertain.

In 1916 Bachmann published a paper titled “The Inter-Auricular Time Interval” in the American Journal of Physiology. Bachmann measured activation times between the right and left atria and demonstrated that interruption of a distinct anterior interatrial muscular band resulted in delayed left atrial activation. He concluded that this band constituted the principal route for rapid interatrial conduction.

Subsequent anatomical and electrophysiological studies confirmed the importance of the structure described by Bachmann, which came to bear his name. Bachmann’s bundle is now recognized as a key determinant of atrial activation patterns, and its dysfunction is associated with interatrial block, atrial fibrillation, and abnormal P-wave morphology. His work remains foundational in both basic cardiac anatomy and clinical electrophysiology.

Sources and references

1. Bachmann G. “The inter-auricular time interval”. Am J Physiol. 1916;41:309–320.

2. Hurst JW. “Profiles in Cardiology: Jean George Bachmann (1877–1959)”. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:185–187.

3. Lemery R, Guiraudon G, Veinot JP. “Anatomic description of Bachmann’s bundle and its relation to the atrial septum”. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:148–152.

4. "Remembering the canonical discoverers of the core components of the mammalian cardiac conduction system: Keith and Flack, Aschoff and Tawara, His, and Purkinje" Icilio Cavero and Henry Holzgrefe Advances in Physiology Education 2022 46:4, 549-579.

5. Knol WG, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, et al. “The Bachmann bundle and interatrial conduction” Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:127–133.

6. “Iatrogenic biatrial flutter. The role of the Bachmann’s bundle” Constán E.; García F., Linde, A.. Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén, Jaén. Spain

7. Keith A, Flack M. The form and nature of the muscular connections between the primary divisions of the vertebrate heart. J Anat Physiol 41: 172–189, 1907.

"Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc., and the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily" wish to thank all individuals who donate their bodies and tissues for the advancement of education and research”.

Click here for more information

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 1519

This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

Francesco Todaro

Francesco Todaro (1839 – 1918) Italian physician and anatomist born in Tripi, a village in the province of Messina, Sicily.

While still a medical student at the University of Messina, he joined the Garibaldini as a volunteer and fought at Corriolo and Milazzo during the campaign for Italian unification in 1860. After completing his medical degree, he pursued further anatomical training in Florence, studying under prominent figures including Moritz Schiff and Filippo Pacini (1812 – 1883) focusing his research myocardial and valve anatomy.

In his 1865 publication, "Novelle ricerche sopra la struttura delle orecchiette del cuore umano e sopra la valvola di Eustachio" Todaro described a fibrous extension of the valve of the inferior vena cava (Eustachian valve) starting at the point where the Eustachian valve and the valve of the coronary sinus (Thebesian valve) appear to merge. This structure later became known eponymically as the tendon of Todaro, component of the boundaries of the triangle of Koch, site for the atrioventricular node.

In page 33 of this publication Todaro states: “e perseguitatolo, con ogni accuratezza, in mezzo alle fibre muscolari del sotto, l'accompagnai fino al pilastro posteriore della fossa ovale, da ove mi accertai entrare pel corno posteriore, che qui ha origine, nella valvula di Eustachio, percorrendola in tutto il suo margine libero. Ho confermato dopo, questa osservazione, in molti altri casi ; ed ho trovato sempre costante, il tendine, anco quando la valvula d'Eustachio è quasi manchevole.” “I followed it to the posterior pillar of the oval fossa, from where I confirmed that it entered through the posterior horn, which originates here, into the Eustachian valve, following its entire free margin. I have subsequently confirmed this observation in many other cases, and have always found the tendon to be constant, even when the Eustachian valve is almost missing.”

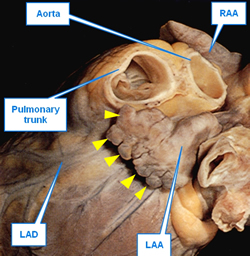

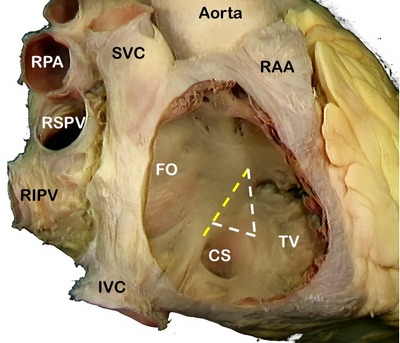

SVC: Superior vena cava, RPA: Right pulmonary artery, RSPV: Right superior pulmonary vein, RIPV: Right inferior pulmonary vein, IVC: Inferior vena cava, RAA: Right atrial appendage, FO: Foramen ovale, TV: Septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve. The yellow line shows the location of the "Tendon of Todaro".

In 1867 he was appointed Professor of Human Anatomy at the University of Messina, and in 1871 he accepted the chair of anatomy at the University of Rome “La Sapienza”, where he remained until his death.

In 1874, Todaro became a member of the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Italy’s foremost scientific academy. He also served as a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy.

Personal note: There are some publications that assert that the tendon of Todaro is rarely seen. That has not been my experience.

Sources:

1. Sopra la struttura delle orecchiette del cuore umano. Todaro F. Stabilimento Civelli Pub. Florence, Italy: 1865. (Italian)

2. TODARO, Francesco. Dorello P. Enciclopedia Italiana. 1937 (Italian)

3. Todaro, Francesco. Treccani Enciclopedia on line.(Italian)

4. TODARO, Francesco. Ottaviani A. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 95. (Italian)

5. Cardiac anatomy primer. McMullen, HL. Am Assoc Thorac Surg.

- Details

- Hits: 5610

This article is coauthored by Randall K. Wolf, MD and Efrain A. Miranda, PhD

Can there exist a unified theory that deciphers the mechanisms for cardiac arrythmias and atrial fibrillation (AFib) that can also explain the results of various catheter-based and surgical-based treatments? Based on anatomical and physiological study of the heart and it’s nervous system, we believe the answer is yes.

While we have learned not to expect everyone to be persuaded by the argument we will be presenting, we suggest, nevertheless, this argument does deserve careful and dispassionate consideration for it provides a model which explains results in the treatment of AFib, and should not be ignored. The epiphany that shed light on a possible unifying mechanism came during multiple cases of left atrial electrical testing during minimally invasive surgical pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) in patients who had multiple previous catheter-based PVI ablation procedures.

Over the years we have evolved our view of the anatomical structures and processes that control the beating rhythmic activity of the heart. Additional and complementary information can be found following the links in the article.

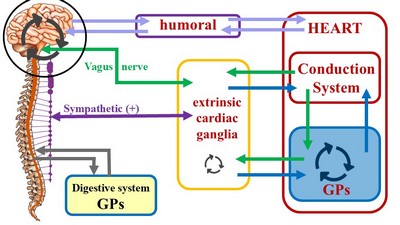

First, we need to define two terms in reference to the heart: “Intrinsic” and “Extrinsic”. An intrinsic structure is found within the boundaries of the heart, that is, within the parietal pericardium. Extrinsic means that the structure about is found outside the parietal pericardium.

The most well-known intrinsic component is what we know as “the conduction system of the heart”. The classic description of the conduction system of the heart emphasizes this cardiomyocyte- based component and refers to a group of specialized cardiac muscle structures that serve as pacemakers and distributors of the electrical stimuli that make the heart beat coordinately. It is important to stress the fact that this primary "conduction system of the heart" is not formed by nerves, but rather by specialized cardiac muscle cells. Probably the reason so much emphasis is placed on the conduction system of the heart is the use of the electrocardiogram as a clinical diagnostic tool since William Einthoven (1860 - 1927) introduced the EKG in 1901.

The second (quite complex) component of this system has been forced to take a secondary place, and in many cases ignored. We refer to the modulating activity on the heart by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), with its two subsystems, sympathetic and parasympathetic.

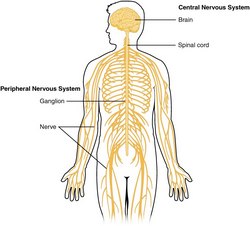

Unlike the conduction system of heart, which is purely intrinsic, the cardiac autonomic system is both extrinsic and intrinsic. The classic architecture described is a two-neuron system, where an extrinsic preganglionic neuron located in the central nervous system (CNS) connects with an extrinsic postganglionic neuron found in the sympathetic chain and ganglia located in the superficial and deep cardiac plexuses close to the aorta and pulmonary trunk.

The cardiac ANS has an intrinsic component formed by ganglionated plexi (GPs) and nerves found within the walls of the myocardium and in epicardial areas of the heart which contain fat. The main location of these GPs is close to and around the great vessels. These ganglionated plexi are the basis for the complex rhythmicity responses of the hear. In fact, several researchers call these intracardiac plexuses the "Little Brain of the Heart". Failure of the ganglionated plexi are the basis of many cardiac arrythmias, including atrial fibrillation.

The inclusion of the cardiac ganglionated plexi into this picture has led us to propose a different ANS organization for those organs that have rhythmicity, be it a beat (heart) or peristalsis (digestive system, ureters, urethra, etc.). For a more detailed explanation follow this link to another article on this topic.

These cardiac intrinsic ANS component are responsible for the complex reflexes that increase or decrease both the heartbeat and the force of contraction of the heart muscle in response to variations in volumetric pressure in the atria and chemical variations in the blood caused by alcohol, caffeine, drugs, dehydration, etc. A more detailed explanation can be found in the following Houston Methodist DeBakey CV Live video. Click on the video to start it or you can go directly to YouTube by clicking here. The main content start at 2 minutes:

The cardiac ANS has important communication with the brain centers responsible for mood and emotions. It is important to note that emotional response is linked to visceral activity (glands and viscera), and this includes the heart.

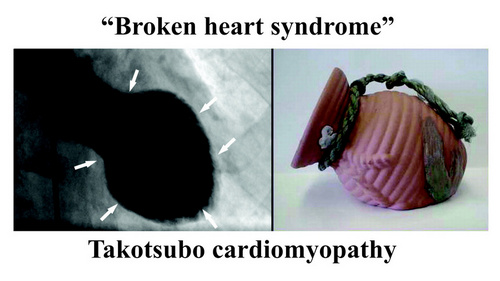

Also, the ANS/GPs complex is not separated from the higher functions of the forebrain. Cechetto (2005) explains how the forebrain (conscious) activity influences the spinal cord and the ANS by pathways that include the limbic system, insula, amygdala, and lateral hypothalamus. These pathways and communications can certainly explain arrythmias caused by stress and anxiety and pathologies such as the “broken heart syndrome” (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy).

Note: "Broken heart syndrome" or "stress cardiomyopathy" is also known as "Takotsubo cardiomyopathy". This is because the shape of the heart in this condition changes and resemble a Japanese octopus (tako) trap (tsubo). For more information on this condition, click here.

Sources and references

1. Kawashima, T. The autonomic nervous system of the human heart with special reference to its origin, course, and peripheral distribution. Anat Embryol (2005) 209: 425–438

2. D. F. Cechetto, "Forebrain Control of Healthy and Diseased Hearts," Chapter in "Basic and Clinical Neurocardiology", J. Armour and J. L. Ardell, Eds., Oxford University Press, 2004.

3. Kandel ER, Koester JD, Mack SH, Siegelbaum SA. Principles of Neural Science. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2021.

4. Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 42nd ed. London, UK: Elsevier; 2021.

5. Haines DE, Mihailoff GA. Fundamental Neuroscience for Basic and Clinical Applications. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

6. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physiology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021.

7. Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, et al. Neuroscience. 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2018.

8. Felten DL, Maida MS. Netter’s Atlas of Neuroscience. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021.

9. Wolf, RK; Miranda, EA. Minimally Invasive Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation: A New Look at an Old Problem. 2024 Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

10. Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Harvard.edu

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 4674

UPDATED: The left atrial appendage (LAA) is an embryological remnant of the development of the heart. It represents the primitive left atrium (LA) which is then “pushed to the side” by the development of the final (adult) stage of the LA. While the LAA is thin, tubular, tortuous, and presents with convoluted muscular walls, the adult LA has smooth walls and is considered to be a dilation of the terminal portion of the veins that enter the LA, hence the name “sinus venarum”, another term for the atria. The LAA is also known as the "left atrial appendix", or the "left auricle".

The anatomy of the LAA is presented in the video included at the end of the article, but there are some details that are important to discuss in the involvement of the LAA in the creation of thrombi and emboli in the presence of atrial fibrillation (AFib).

LAA shape and size

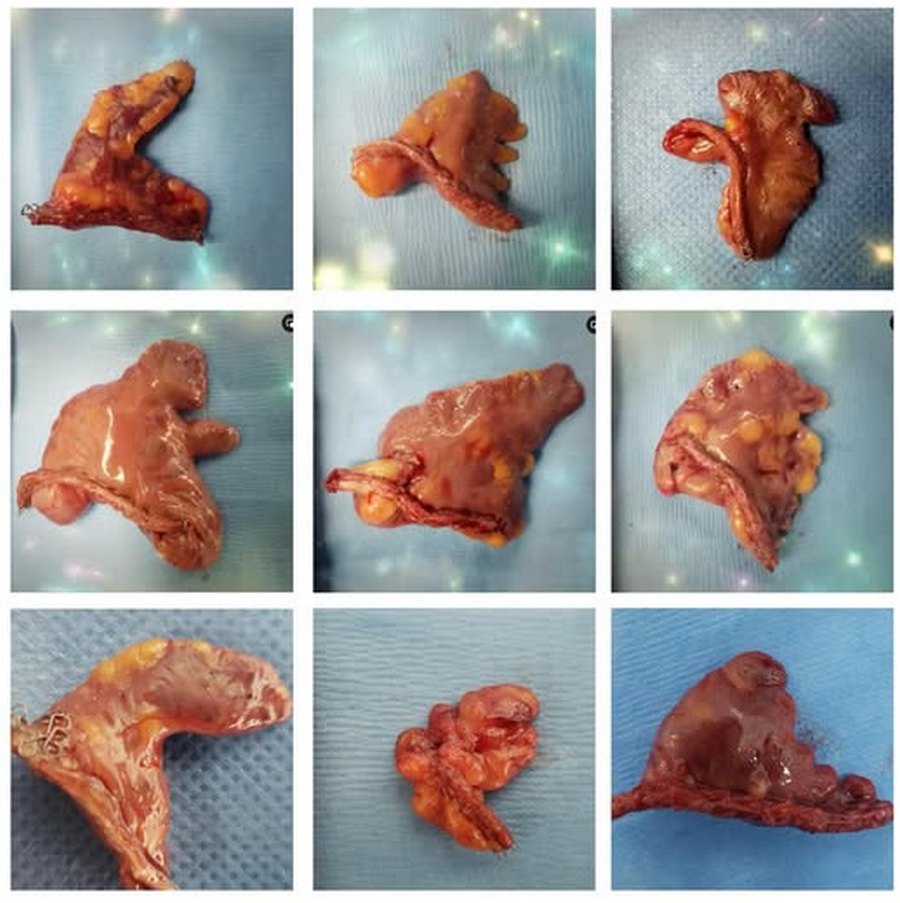

The LAA has important anatomical variations, with different shapes that anatomists and physicians have tried to consolidate in groups such as: chicken wing, cactus, windsock, cauliflower, etc. The fact is that recording the shape of the LAA is subjective. as the evaluation depends completely on the observer.

Researchers have tried to determine what shape can lead to a higher potential for stroke-producing emboli when AFib is present. A recent study by Dudzińska-Szczerba (2021) and an editorial by Yong Shin (2021) states that the shape itself is not a good predictor, but the distance between the LAA ostium and the first bend of the LAA is indeed a good predictor. The longer the distance there is increased potential for thrombus and emboli formation.

Left atrial appendage shapes. Courtesy of Sandra Fezzat Schrameyer

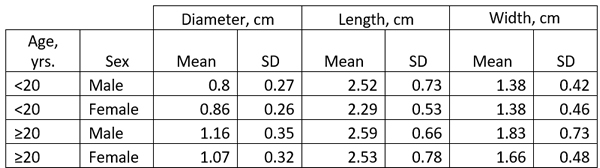

The size of the LAA has been studied in detail and it ranges ranging from 0.3 cm to 2.0 cm in males, and 0.3 to 1.8 cm in females. (Venoit, 1997), as shown in this table.

The LAA ostium

The LAA ostium is the communication between the LA and the LAA, it is generally oval in shape and its size is variable. The ostium is in some cases slit-like, or an elliptical-shaped variant, “smiley”, and even small circular (DeSimone, 2015; Cabrera, 2014). A study by Wang (2010) classified the LAA ostium into five types: oval (68.9%), foot-like (10%), triangular (7.7%), water drop-like (7.7%), and round (5.7%). It is interesting that devices that are used to occlude the LAA ostium are round and that is only 6% of the population reported in the Wang (2010) study. In a study by Su (2006) it was found that 100% of the specimens studied the LAA ostium had an oval shape with the mean diameter of the opening of 17.4 mm with a range between 10-24.1 mm).

In reference to LAA ostium occluders Su (2006) states that "These percutaneous devices / systems,however, have a round shape to fill or cover the LAA ostium. A previous study and our study show that the shape of the LAA ostium is consistently elliptical rather than round. This suggests that to seal the LAA orifice adequately without oversizing, devices may need to be elliptical for a snug fit. A round implant over an oval-shaped orifice may leave crevices on either side of the implant, leading to incomplete sealing of the orifice."

Lobes

The LAA can also present with different dilations called “lobes” these can range from zero to three or four.

Muscular Wall Structure

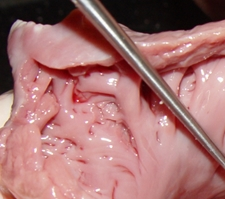

The LAA has internal ridges that form a muscular meshwork. The term used to describe these is “trabeculated”. It makes sense that in the case of atrial fibrillation, the slow to non-existent flow of blood within the deep recesses of the trabeculated muscular wall of the LAA will cause blood to pool and coagulate, forming thrombi. The presence of these LAA trabeculations have been found to be associated with stroke risk by Dudzińska-Szczerba (2021). The accompanying image shows the trabeculations in a cow's LAA. They are not as deep or as convoluted as those found in a human heart.

Crenellations

This is a rarely used term. It is a pattern along the top of a fortified wall, as in a castle, forming multiple, regular, rectangular spaces. These crenellations are found in the edge of the LAA compounding the irregularity of the internal wall and increasing the chance for thrombus formation and stroke-inducing emboli. Crenellations are shown by yellow triangles in the first image in this article.

Function of the LAA

As stated, the LAA is an embryological remnant, but it does have a function in the adult. It generates a peptide involved in the control of salt in the circulatory system. This is the atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a hormone that is secreted by both the right and left atria and their appendages in response to circulatory volume and pressure changes. ANP helps the elimination of excess sodium through the kidneys (natriuresis), control of urine elimination (diuresis), and antifibrotic and antihypertrophic effects within the heart (Sandeur, 2023)

While removing both the right and left atrial appendages could cause ANP deficiency, surgical removal or exclusion of only the LAA does not cause an ANP problem (8).

Involvement of the LAA in AFib

The LAA is an electrically active structure. The cardiomyocytes that form its walls have automatic activity and it has been described as an area that can trigger AFib. The accompanying video shows an LAA that has been separated from the heart (in this case using a surgical stapler) and it can be seen how the LAA continues fibrillating on its own. Video courtesy of Dr. Randall K. Wolf

This is the why LAA exclusion is a must in the case of AFib and potentially in any cardiovascular procedure where the pericardial sac is opened (this is a subject for discussion).

The problem is that devices that only occlude the LAA ostium do not electrically isolate the LAA wall from the LA wall, leaving this potential AFib-producing connection intact. Just occluding the LAA ostium is not a solution for atrial fibrillation, it just reduces the risk of stroke.

Personal note: In May 5th, 2020 Dr. Randall K. Wolf invited me to a live webcast where we reviewed the anatomy of the left atrial appendage, the problems the LAA can cause in atrial fibrillation leading to stroke, and the reasons for its exclusion in AFib surgery. This video is next. You can watch other videos on the topic here. Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. “Anatomy of the Normal Left Atrial Appendage: A Quantitative Study of Age-Related Changes in 500 Autopsy Hearts: Implications for Echocardiographic Examination” Veinot, JP; et al. 1997 Circulation; 96:3112–3115

2. “A Review of the Relevant Embryology, Pathohistology, and Anatomy of the Left Atrial Appendage for the Invasive Cardiac Electrophysiologist” De Simone, CV, et al. J AFib 2015; 8:2 81-87

3. “Left atrial appendage: anatomy and imaging landmarks pertinent to percutaneous transcatheter occlusion” Cabrera,JA; Saremi, F; Sanchez-Quintana, D. 2014 Heart 2014 100:1636-1650

4. Left Atrial Appendage Studied by Computed Tomography to Help Planning for Appendage Closure Device Placement” Wang Y. et al. J Cardiovasc Electrophyisiol 2010 21:9 973-982

5. IIs the Left Atrial Appendage (LAA) anatomical shape really meaningless measure for stroke risk assessment? Shin, SS; Park, JW. Int J Cardiol 2021 May 1:330:80-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.02.047.6. “Assessment of the left atrial appendage morphology in patients after ischemic stroke” Dudzińska-Szczerba, K. et al. Int J Cardiol 2021 330:65-72

7. “Atrial Natriuretic Peptide” Sandeur, CC; Jialal, I. Stat Pearls 2023. StatPearls https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562257/

8. Personal communication, Dr. R. Wolf 2023

9. "Slide Atlas of Human Anatomy" Gosling, J.A.; Whitmore, I; Harris, P.F.; Humpherson, J.R., Et al; ISBN: 0723426570 Hong Kong: Times Mirror, 1996

10. "Atrial and brain natriuretic peptides: Hormones secreted from the heart" Nakagawa Y, Nishikimi T, Kuwahara K. Peptides. 2019 Jan;111:18-25.

11. "Occluding the left atrial appendage: anatomical considerations" Su, P; McCarthy, KP; Ho, SY. 2008 Heart 94:1166–1170

Thanks to Sandra Fezzat Schrameyer for the image of the different shapes of the LAA.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 11644

The medical term "ganglion" derives from the Greek γάγγλιο (gánglio) and means "a knot". It was initially used by Hippocrates of Cos (460 BC - 370 BC) to denote a small mass (tumor) under the skin. The term is still used in medicine to name small synovial cysts found near joint or around small tendons. The term was later used by Galen of Pergamon (129 AD - 200 AD) to name small nervous masses. The common use for the term in tendons and nerves is that the Greek made no distinction between these structures calling them [νευρών] (nevrón) meaning both tendon or sinew and nerve. The plural form for ganglion is "ganglia".

Today, the term "ganglion" is mostly used to denote a an encapsulated aggregation of neuronal cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system that serves as a relay, integration, or sensory transduction site. A ganglion may be part of simple and complex reflex circuits. A ganglion has an external capsule formed by connective tissue, neuronal bodies, and supportive neuroglial cells.

This term should not be used to refer to structures found in the central nervous system (CNS). An aggregation of neuronal bodies in the CNS is called a "nucleus", the plural form is "nuclei".

When intercommunicated, ganglia can form complex networks (plexi) inside the muscular layers of organs that have rhythmicity, such as the enteric and cardiac ganglionated plexi. These neuronal networks function as autonomic relays and integration sites, reducing the workload of the CNS.

Interestingly, ganglia can be found in small animals that lack a vertebrate-type CNS, illustrating their function in complex reflexes. Some examples are:

- Echinodermata (sea stars, brittle stars/ophiuroids)

- Cnidaria (jellyfish, sea anemones)

- Flatworms (although it does have a cephalic ganglion that some contend is a "brain"

Sources:

1. Skinner, "The Origin of Medical Terms" 1970. William and Wilkins

2. Standring S, ed. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 42nd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

3. Anderson, Douglas M "Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary"; ISBN: 0721655777 USA: W.B. Saunders, 1994.

4. Ross, Michael H, et al. "Histology: A Text and Atlas"; ISBN: 0683073699 Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995

5. Haines, Duane E. "Neuroanatomy: An Atlas of Structures, Sections and Systems"; ISBN: 9780781746779 Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

6. Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

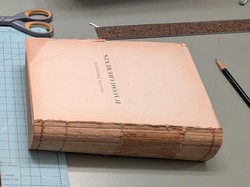

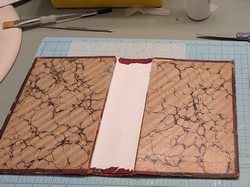

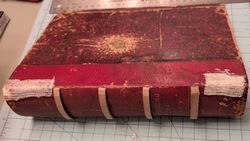

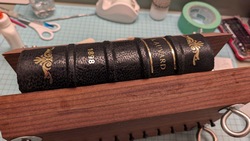

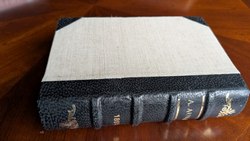

I recently received a book from Chile. This book is in French and is titled “Traité D’Accouchements” (Treatise of Childbirth) or a “Treatise in Obstetrics” and was published in 1898 in Paris. The author is Dr. Pierre-Victor Alfred Auvard, (1855 - 1940), a French Obstetrician and Gynecologist.

The book belonged to the library of San José Hospital. The Old San José Hospital is a former hospital located on San José Street, next to the General Cemetery of Santiago, in the Independencia district of Santiago, Chile. Built between 1841 and 1872, it functioned as a hospital until 1999, when the new San José Hospital was built. Parts of this hospital are now being demolished and a new one will be built in its place, but the old books from the library were discarded without a second thought. An engineer in charge of the new construction managed to rescue some of these books, and one of them was brought from Chile to the United States by another friend of mine, Carlos Verdugo, a classmate.

The book was in terrible condition, with a barely legible title, the spine was broken, and the signatures (groups of pages that together from the text block) separated as the threads that kept the book together were torn. Bookbinding and book repair being another one of my hobbies, I undertook the task and now it will be added to my collection. Here are some pictures of the process. Click on the image to see a larger version.

In one of its pages, the book has an old and barely legible stamp the reads “Manuel Casanueva del C.” A short search indicated that this was the Ex-Libris stamp of a Chilean surgeon Dr. Manuel Casanueva del Canto. Of course, I had to do some research on the past owner of this book.

Manuel Casanueva del Canto was born in the city of Linares, Chile on July 5, 1908. From 1925 to 1931 he coursed 1st to 6th year of medical school at the Medical College of the University of Chile (where I studied). At that time the College of Medicine was in the Independencia neighborhood in the city of Santiago. In 1930 he obtained his medical license.

The repaired book in my library

Between 1930 and 1931 he was a surgical resident at the Hospital San Francisco de Borja (where I was a patient as a child), passing through Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine and Surgery, and Obstetrics, obtaining his surgical degree in May 1932. His thesis for the degree was entitled “Pathological Anatomy: Inflammatory alterations of the gallbladder”.

As a surgeon, he worked at the Santiago Military Hospital, Central Emergency Services, and the Central Trauma Hospital. In 1952, going back to his roots, he moved to the Surgical Department of the University of Chile at the Hospital “Jose Joaquin Aguirre”. This hospital is on the same campus as the Medical College where he studied.

In 1955 he applied for (and obtained) the position of Professor Extraordinaire of Pathological Surgery in the Medical College of the University of Chile. At this time, he already had a great teaching career, several medical awards, authored the book “Practical Blood Transfusion” in 1939 as well as co-authored several medical books and over 81 papers.

He became Chief of Surgery at the Jose Joaquin Aguirre Hospital and in 1961 he invited Pablo Neruda, Chilean Nobel Prize winner in literature, to lecture at the hospital.

In 1975 Editorial Andres Bello published his book “Surgery”, two volumes in Spanish. I have not been able to trace this book. Not much is known of him after this date. No photography or portrait has been found.

He married Maria Yolanda Carrasco Coral (date unknown), they had three children: Maria Cristina, Isabel, and Manuel Luis.

He died on February 13, 1981, in the city of Viña del Mar, and is buried in Santiago, Chile. Further research indicated that this book I received as a gift was donated to the library of Hospital San José by Dr. Casanueva where it eventually was discarded, rescued, transported to the US, and repaired.

I hope this article reaches the Casanueva del Canto family in Linares (today they probably are Casanueva Carrasco and/or Casanueva Iommi) and they can help me update this research, and hopefully a photograph of Dr. Casanueva del Canto. To this end, here is the Spanish version of this article.

- Details

- Written by: Efrain A. Miranda, Ph.D.

- Hits: 5651

Figure 1: AV node as depicted by Sunao Tawara

The atrioventricular (AV) node is a critical component of the conduction system of the heart, serving as the only (normal) electrical connection between the atria and the ventricles. By delaying atrioventricular transmission by 1/10th of a second, the AV node allows the heart to work as a pump.

The AV node is situated in the inferior portion of the interatrial septum. It was discovered in 1906 by Sunao Tawara, who identified it as a discrete small structure located at the atrioventricular junction and demonstrated continuity of the AV node with the His–Purkinje system (see image 1).

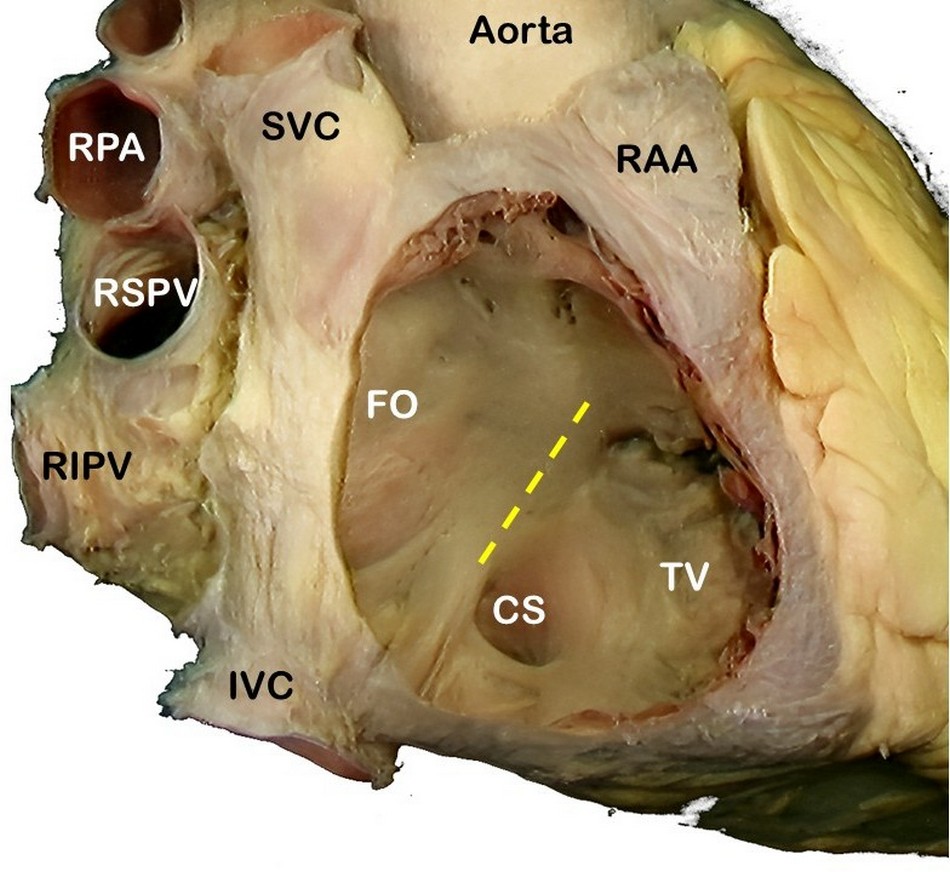

The AV node is a located in the “Triangle of Koch” (see note), a region bound by the tendon of Todaro, the septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve, and the ostium of the coronary sinus (see image 2). Its blood supply is by way of the AV node artery, a branch of the right coronary artery (RCA) that arises usually at the crux cordis, the point of division of the RCA into the posterior descending artery and posterolateral artery.

Image 2: SVC: Superior vena cava, RPA: Right pulmonary artery, RSPV: Right superior pulmonary vein, RIPV: Right inferior pulmonary vein, IVC: Inferior vena cava, RAA: Right atrial appendage, FO: Foramen ovale, TV: Septal leaflet of the tricuspid valve. The yellow line shows the location of the "Tendon of Todaro". The complete triangle is the triangle of Koch.

The ventricles are isolated from the atria by connective tissue that forms an electrical barrier between. This barrier is sometimes called the “skeleton of the heart” a misnomer that does not explain the reason for its presence. If there was no barrier, the atria and ventricles would all contract at the same time and the pumping action of the heart would not exist.

The only place where the electrical impulse can pass from the atria to the ventricles is through the AV node. Because of the specialized cardiomyocytes that form the node, the transmission of the impulse is delayed by one tenth of a second, enough that the ventricles will contract after the atria contract, causing blood flow through the heart.

Note: The "triangle of Koch" is eponymically named after Walter Eduard Carl Koch (1880 - 1962) a German physician and pathologist.

Sources and References:

1. Markowitz, MM; Lerman BL. A contemporary view of atrioventricular nodal physiology. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018 Aug;52(3):271-279.

2. Efimov IR, Nikolski VP, Rothenberg F, Greener ID, Li J, Dobrzynski H, Boyett M. Structure-function relationship in the AV junction. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004 Oct;280(2):952-65.

3.Fumarulo I, Salerno ENM, De Prisco A, Ravenna SE, Grimaldi MC, Burzotta F, Aspromonte N. Atrioventricular Node Dysfunction in Heart Failure: New Horizons from Pathophysiology to Therapeutic Perspectives. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2025 Aug 15;12(8):310.

4. Anderson RH, Sánchez-Quintana D, Nevado-Medina J, Spicer DE, Tretter JT, Lamers WH, Hu Z, Cook AC, Sternick EB, Katritsis DG. The Anatomy of the Atrioventricular Node. J of Cardiovasc Development and Disease. 2025; 12(7):245.

5. Tawara, S. Das Reizleitungenssystem des Säugetierherzens : eine anatomisch-histologische Studie über das Atrioventrikularbündel und die Purkinjeschen Fäden 1906 J Fischer pub. courtesy of archive.org

6. "Tratado de Anatomia Humana" Testut et Latarjet 8th Ed. 1931 Salvat Editores, Spain

7. Anderson, Robert H. MD; Becker, Anton E. MD. "Slide Atlas of Cardiac Anatomy" 10 volumes London: Gower Medical Publishing, 1985. (out of print)