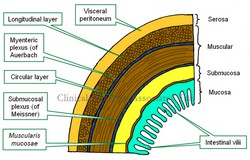

Layers of the GI tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is formed, with a few exceptions, by four concentric layers of tissue. These are, from deep to superficial, the mucosa, submucosa, muscular (or muscularis) and the serosa layers. This is the simplified version. The fact is that there are more sublayers.

The mucosa layer is characterized by the presence of intestinal villi, which in the stomach and small intestine contribute to absorption of the digested food. The mucosa has a thin layer of connective called the "lamina propia" and external to it a thin layer of smooth muscle, the muscularis mucosae.

The submucosa layer is formed by irregular connective tissue and contains on its most external region a plexus of nerves and neurons, the "submucosal plexus of Meissner", which provides parasympathetic innervation to glands and the muscularis mucosae.

The muscular layer, also known as the "muscularis" is composed of two sublayers of smooth muscle. The deep layer contains circular fibers and is known either as the "circular muscle layer" or the "muscularis interna", the superficial layer contains longitudinal smooth muscle fibers and is known as the "longitudinal muscle layer" or the muscularis externa. Between both muscle layers lies the "myenteric plexus of Auerbach", a layer of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves and neurons that provides nerve supply to the muscular layer. The combined action of this plexus on the muscular layer is responsible for peristalsis.

The serosa layer is the outer or external layer and is formed by a layer of peritoneum. As such, this layer can also be called "visceral peritoneum".

There are variations from GI organ to GI organ in the arrangement, content, glands, thickness of the layers, etc. The most important differences can be found in the thoracic esophagus and most of the rectum which are devoid of a serosa layer, and in the stomach, where there is a third muscular layer, deep to the circular layer, called the "oblique layer" that contributes fibers to the lower esophageal sphincter found at the esophagogastric junction.

An important point to make is the presence of two interconnected ganglionated plexuses that are represented in the GI tract by the submucosal plexus of Meissner and the myenteric plexus of Auerbach which form the GI intrinsic autonomic nervous component . These two plexuses extend from the esophagus to the rectum and allow for the GI tract to operate almost independently from the extrinsic autonomic nervous system which moderates their activity. Ganglionated plexuses are present in organs that have rhythmic activity, such as peristalsis. Ganglionated plexuses are also present in the heart.

Sources:

1. "The bowel and beyond: the enteric nervous system in neurological disorders" Rao, M & Gershon, M. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Sep; 13(9): 517–528.

2. "Advances in Enteric Neurobiology: The “Brain” in the Gut in Health and Disease" Kulkami, S et al. Journal of Neuroscience 31 October 2018, 38 (44) 9346-9354

3. "The Brain-Gut Connection" John Hopklins Health

4. "Think Twice: How the Gut's "Second Brain" Influences Mood and Well-Being" Hadhazy, B. Scientific American February 2010

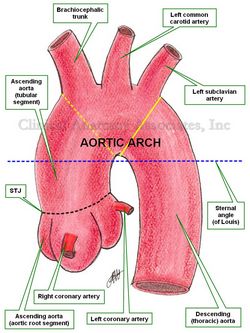

Images property of:CAA.Inc.Artist:Dr. E. Miranda