This article is part of the series "A Moment in History" where we honor those who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research.

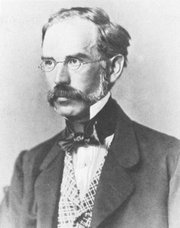

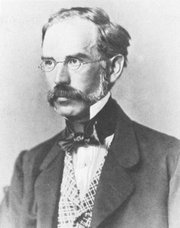

Vaclav Treitz

As part of the redesign of this website we added a sidebar called "A Moment in History". The objective is to create a series of articles to honor those individuals who have contributed to the growth of medical knowledge in the areas of anatomy, medicine, surgery, and medical research. Later in the development of the series we became aware of other individuals who have contributed in different ways, but still added their life work to the advancement of medical knowledge, as is the case of Marcia Croker Noyes (1869-1946).

Who would not be moved by the work of Allesandra Gilliani (1307-1326), who is probably the first woman dissector in the history of Human Anatomy, with a tragic short life and a love story.

We also decided to add to this series Moments in History that have left a mark on health care, such as "The First Use of Anesthesia in Surgery", or the story of how many individuals and unknown, anonymous children helped to rid the Americas from the scourge of smallpox, in "The Balmis Expedition",

Another line of articles in this series are those that honor individuals who have used anatomical and surgical knowledge to further other areas of human knowledge, such as that of Juan Vucetich, who used the anatomical differences in fingerprints to create the science of dactiloscopy.

Yet another line of articles are those that are more personal and dear to the contributors of "Medical Terminology Daily", such as "The Ephraim McDowell House of Museum", or "Interesting Discovery in and Ex-Libris".

Recently, I had to work in the Wangensteen Historical Library researching rare and antique medical books. The highlight of this work was to be able to read books by authors whose names are attached as eponyms to anatomical landmarks (Ligament of Treitz, Hesselbach's Triangle), pathologies (Koplik's spots), surgical procedures (Billroth I and II), medical maneuvers (Heimlich maneuver), and surgical instruments (Finochietto retractor). Of course, the names given here are but a small sample of what has been written to date.

As of today this series is now searchable, all you have to do is type "A Moment in History" in our search page, click on the "A Moment in History" link at the top of the sidebar, or click here

The image in this article is that of Dr. Vaclav Treitz. His eponymically named Ligament of Treitz is the most read article in this blog.

Original image, public domain, courtesy of Wikipedia.org.