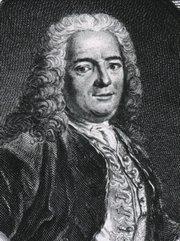

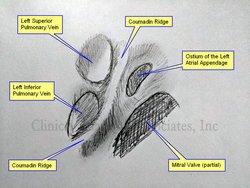

Figure 1: Vesalius Fabrica Portrait

Recently I acquired the 1925 book “The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius” by Marion Harry Spielmann (1858-1948). M.H. Spielmann was a well-published Victorian art scholar and critic. At the end of this article you can find the bibliographical information on this book.

The book is a serious detailed research of the known paintings, lithographies, sculptures, and medals that show the likeness of Andreas Vesalius, the date of publication and the author’s commentary on each one.

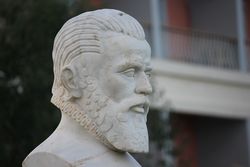

Andreas Vesalius is known as the “Father of Modern Anatomy”. He pushed for a description of the structure of the human body as seen in a dissection, going against the trend at the time where the anatomy was that described by Galen of Pergamon in his books. Galen’s anatomy was based on animal dissection and not a lot of human dissection. Furthermore, the lecturer would read from the book and the demonstrator pointing at the structures ignoring the discrepancies between the book and the body. For additional information and images click here.

Vesalius opus magnum (great work) was the publication in May 1543 of one of the most famous books in medical history. The title of the book is “De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Libri Septem” (Seven Books on the Structure of the Human Body). The book is now known as the “Fabrica”. This has led numerous artists to paint his likeness, many times based on past images or sometimes from pure imagination. The latest modern edition of the Fabrica was published in 2014.

We do know of only one portrait that depicts Vesalius’ likeness at the time of printing (1542) and that is the second image in the Fabrica of 1543 (figure 1) This image was carved in a pear wood block later used for printing. The woodblock indicates the date of carving (1542) and the age of the great anatomist that year (28). The sketch from which the block of wood was carved is most surely made by Jan Stephan Van Calcar (1449-1546). There is only supposition as to who was the artist that carved the woodblock, and there are several research papers on the subject. The best suggestion is that the woodcarvers were Francesco Marcolini (1505-1560) and Domenico Campagnola (1500-1564), both mentioned in a paper by Jaffe and Buchanan (2016). Campagnola is actually thought to be the woodcarver for the title page of the 1543 Fabrica.

The Iconography book goes into great detail on this image of the great anatomist, and dedicates a detailed description of the title page of the 1543 and the 1555 editions of the Fabrica, descriptions that I can only encourage to be read by researchers interested in the life and works of Andreas Vesalius. The book can be read online the Internet Archive here. The book is written mostly in English, but has an introduction in French.

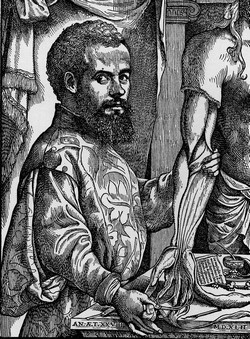

Figure 2: 1555 Fabrica Title Page

“The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius” is a rare book, it is not easy to find, and probably the most important characteristic of the book is not mentioned in the many descriptions of the book found on the Internet, medical libraries, and antiquarian booksellers websites: The book originally included a separate, folded-in-four, high-quality linen paper print of the title page of the 1555 Fabrica. Most of the books found today have lost this print. Figure 2 shows a scan of the print found in the book I acquired. A 4.5 Mb watermarked actual size of this print can be seen here. If you want to download it, you can right click on the image and then click on "Save As".

This reprint of the Fabrica’s title page was done using the 1555 original woodblock, which makes it priceless. As shown in the accompanying image, the page leaves blank the two places where the title of the book and the dedication to the king and printer markings where placed. These would have been prepared in separate type and rearranged for a different use after printing. The print measures 16 7/8 by 12 1/4 inches (31.1 by 42.9 cms) The woodblock of the title page of the 1555 Fabrica was last used in 1934 when it was used to print the 1934 edition of the Icones Anatomicae, and then returned to the Louvain University in Belgium where it was destroyed by the German army in 1940. The Icones Anatomicae was the last print using the original woodblocks.

The rest of the original woodblocks was burned during a WWII bomb raid on July 16, 1944.

The following information is from the Stanford Library and it is one of the few that indicate the existence of the reprint of the 1555 Fabrica title page in an envelope pasted on the book cover reverse.

Author/Creator: Spielmann, M. H. (Marion Harry), 1858-1948.

Subject: Vesalius, Andreas, 1514-1564. History of Medicine. Physicians. 1500s

Genre: Biographical Information. Historical Works. Portraits

Bibliographic information:

Date: 1925

Series: Research studies in medical history ; no. 3, 1925

Note: Includes index. Title-page of De humani corporis fabrica libri septum by Andreas Vesalius, Second edition, 1555 printed direct from the original wood block in the pocket on verso of cover.

Personal Note: I am working on updating my library catalog to reflect the latest book acquisitions and gifts received. Dr. Miranda.

Sources:

1. “The Iconography of Andreas Vesalius” M.H. Spielmann. The Wellcome Historical Medical Museum London. John Bale, Sons & Danielson Ltd.

2. “The Andreas Vesalius Woodblocks: A Four Hundred Year Journey from Creation to Destruction” Acta Med Hist Adriat 2016; 14(2);347-372

3. "The identity of the artists involved in Vesalius Fabrica 1543” Guerra, F. (1969) Medical History, 13(1), 37.